My interest in this book was piqued by hearing the author talk about it on a podcast. The anecdotes he shared were edifying. The same is true of the book as a whole. This is not a hagiography. The faults of the church at various points in its history were examined. Nor is this an academic history; it is written to edify. Each chapter is focused not only on an era of the church but on key issues that emerged in those eras. There is much to learn from this book. But in the end, it evokes thankfulness to God for his faithfulness to the church that has gathered on Capitol Hill over many lifetimes.

Vlach, Michael. Chapter 1: “The Importance of the Kingdom,” in He Will Reign Forever

Vlach proposes that “kingdom” is the central theme of Scripture (21). He argues this case by noting that the theme runs from Genesis 1 through Revelation 22, that much of Scripture is focused on the development of the kingdom, that the kingdom is the central theme in Jesus’s ministry (and that of his forerunner, John), and that the kingdom is the focal point of eschatology. Vlach also argues that the themes of covenant, promise and salvation all connect into the kingdom theme. Finally, Vlach acknowledges that God’s glory is the “purpose for which God does what he does,” but he wishes to distinguish this from “a theme of Scripture” (27).

I’m not committed to kingdom as the central theme of Scripture. For instance, I don’t see the need to deny that the glory of God is a theme. But I do affirm that it is right at the heart of biblical theology and that the other major theological themes all connect to it.

Having established the centrality of the kingdom theme, Vlach then turns to define kingdom.

“The concept of ‘kingdom’ includes at least three essential elements:

1. Ruler—a kingdom involves a ruler with rightful and adequate authority and power.

2. Realm—a kingdom involves a realm of subjects to be ruled.

3. Rulership—a kingdom involves the exercise of ruling.” [28]

He insists that all three parts must be present for a kingdom to be present. In the end he follows Alva McClain to define kingdom as “the rule of God over His creation” (30, quoting McClain, The Greatness of the Kingdom, 19).

There are a number of weaknesses in Vlach’s definition of kingdom.

First, realm should not be reduced to subjects. The realm of the kingdom includes land. Ultimately, the entire earth is the realm of God’s kingdom.

Second, Vlach seems to think that requiring ruler, realm, and rulership to all be present argues against a present form of the kingdom. This is clear in his characterization of Luke 19:12, where he argues “the actual kingdom reign occurs when the nobleman returns to his realm of authority.” However, Psalm 110:1–2 indicates that the Son is reigning now even before his return. I would argue that all three elements are present even in the inaugurated but not yet consummate rule of Christ.

This definition doesn’t clearly highlight that the kingdom is God’s rule over His creation through man. The Creation Blessing and the necessity of the incarnation is left to the side in this definition. However, Vlach elsewhere roots the kingdom theme in Genesis 1:26–28. Including the through man aspect of the kingdom seems consistent with what Vlach teaches elsewhere.

Vlach, Michael. “Introducing the Kingdom.” In He Will Reign Forever.

Michael Vlach’s large-scale biblical theological study of the kingdom begins with an outline of what Vlach calls “a new creationist perspective.”

He outlines this perspective in six points (14-16):

“1. A new creationist approach affirms the importance of the material realm in God’s purposes.

2. A new creationist approach affirms that physical promises in the Bible will be fulfilled just as the Bible writers expected.

3. A new creationist approach affirms that the coming new earth will be this present earth purged and restored.

4. A new creationist approach affirms the importance of individuals, Israel, and nations in God’s plans. God works with various groups.

5. A new creationist approach affirms the importance of particular and universal entities.

6. A new creationist approach affirms God’s kingdom will involve social, political, geographical, agricultural, architectural, artistic, technological, and animal elements.”

Vlach also opposes false dichotomies (16):

- “The kingdom is not physical; it is spiritual.”

- “The kingdom is no longer about nations; it is about individuals.”

- “The kingdom is no longer about Israel; it is about Jesus.”

- “The kingdom is no longer national; it is international.”

I agree with Vlach’s new creationist perspective, with his opposition to false dichotomies, and with his opposition to transforming or transcending the Old Testament promise and storyline.

However, in the introduction he also says that the coming of the kingdom is contingent upon “Israel’s acceptance of the Messiah.” On this point I think he is wrong. The passages he cites speak to the restoration of Israel, but none of them prevent an establishment of the kingdom before that restoration. At least at this point, Vlach is not touching countervailing biblical evidence.

Josephus and Jesus: New Evidence for the One Called Christ—A Defense of the Testimonium Flavianum.

The Tyndale House Podcast just alerted me to a new book from Oxford University Press making the case that the Testimonium Flavianum in Josephus is authentic. The book is going for $130 hardcover on Amazon. Or it can be downloaded for free from the author’s website due to the generosity of a donor: Purchase & Free Download – Josephus & Jesus.

Vlach, Michael J. Dispensational Hermeneutics: Interpretation Principles that Guide Dispensationalism’s Understanding of the Bible’s Storyline. Theological Studies Press, 2023.

Insights:

I’m the first chapter Vlach surveys “Key Elements of Dispensationalism’s Storyline.” His survey includes a number of important insights.

- Rightly sees the importance of Genesis 1:26-28 as foundational for the theology of Scripture and rightly sees the centrality of kingdom and glory to the Bible’s theology.

- Rightly sees redemption as encompassing not only individuals but also to all of creation, including ethnicities and nations.

- Understands the covenants as the means by which God brings about his kingdom.

- Recognizes the spiritual aspects of God’s work coexist alongside the material aspects of God’s work. The material aspects are not merely typological but often have eschatological significance.

- Recognizes that an emphasis on a progression from the material to the spiritual in redemptive history may be due to the influence of Platonism and other unbiblical worldviews. This viewpoint is at odds with the Bible’s high view of the importance of material creation, including that of the resurrection body.

- Recognizes God’s role for Israel as the nation through whom God gave the Scripture, through whom the Messiah came, and through whom all the nations will be blessed.

- Affirms the salvation of all Israel in the last day.

- Affirms that the spiritual blessings of the covenants have been inaugurated and also affirms that the material blessings will be fulfilled in the last day. (I don’t like spiritual and material as the distinguishing terms. Spiritual in the Bible usually referrs to the Holy Spirit and his work, rather than to a material/spiritual dichotomy; furthermore, the Holy Spirit was at work in the creation of the material world and will be essential to its recreation—just as he is essential to our personal salvation, sanctification, and glorification.)

- Sees promises in the covenants made with Israel fulfilled in the church, and he sees believing Israel in the present age as part of the church. He also sees the church and Israel as two different kinds of entities. Israel is a nation while the church is a multiethnic body of believers.

- Affirms that Christ will return to rule all the nations.

In chapters 2-4 Vlach turns to what he identifies as the hermeneutics of dispensationalism. This section also contains a number of insights.

- He rightly supports discerning authorial intention.

- He rightly accepts that there are types, symbols, and analogies in the text. He denies that these require a different hermeneutic since grammatical-historical interpretation already recognizes the reality of types symbols, and analogies and seeks to discern their author-intended, contextually governed meaning.

- He recognizes that dispensationalists and non-dispensationalists both operate with the same grammatical-historical hermeneutic. (He does say that non-dispensationalists often abandon this approach when it comes to prophecies about the restoration of Israel, which may be too sweeping a judgment.)

- He notes that Israel came under the covenant curses and the judgment of exile just as the Mosaic covenant and the prophets predicted. He then asks why, if the covenant promises of judgment happened as written, the promises and prophecies about Israel’s future restoration and blessing should be reinterpreted as typological and fulfilled only in the church? This is an insightful point, especially since often the prophecies of restoration are textually linked to Israel’s experience of judgment. It would be most odd then for Israel to only experience the judgment and for the promised restoration to be applied only to a different corporate party that did not experience the judgment.

- He rightly recognizes that turning a promise into a type to be fulfilled for someone other than the person to whom the promise was originally made would violate God’s integrity. “Promises also contain an ethical component. The one making a promise is ethically bound to keep the content of the promise with the audience to whom the promise was made” (40).

- He recognizes that later revelation “does not reinterpret or change the meaning of earlier revelation” (41). I don’t take this as a denial that the NT properly interprets the OT. That denial, if made, would be a problem.

- He affirms that the progress of revelation does not alter promises or change the recipients of the promises, though the beneficiaries of the promises may be expanded through progressive revelation.

- The first coming of Christ did not exhaust prophetic fulfillment; some prophecies await fulfillment at the second coming.

- The reason that some OT prophecies are only partially fulfilled at present is due to the fact that Christ comes twice. We can see this in certain prophecies where within the same passage part of the prophecy was begun to be fulfilled in the earthly ministry of Christ and another part awaits the second coming (cf. Zech. 9:9-10; Isa 61:1-2; Amos 9:11-15).

- Jesus is the “Yes” to OT promises in a complex way:

- Jesus “directly” fulfills some prophecies (73)

- “Jesus is the means for the fulfillment of Old Testament prophecies, promises, and covenants” (73). Vlach explains: “There are predictions about a coming antichrist, temple, Israel, nations, destruction and rescue of Jerusalem, battles between nations, the Day of the Lord, kingdom, resurrection, judgment, etc. While not Jesus, these matters are significant to God’s purposes and Jesus is involved with their fulfillment. These things do not vanish or dissolve into Jesus in a metaphysical way” (p. 74).

- Jesus is the true Israel and national Israel still exists as an entity for which promises will be fulfilled. This is a “both/and” rather than an “either/or.”

- Vlach observes different ways in which Israel is used in Scripture. (1) “an ethnic, national, territorial, corporate entity”, (2) “to the believing remnant of Israel,” (3) “the ultimate representative of Israel.” (76).

- Dispensationalism historically has been Christocentric and Christotelic.

- But it is careful not to “read meanings into texts that are not there” in an effort to be Christ-centered.

- Dispensational Christ-centered interpretation does not find Christ in the text by “adding a hermeneutical move beyond the grammatical historical” interpretation of a text (82).

- The OT should be read from the perspective of a NT believer with the knowledge of how Jesus has fulfilled the law and the prophets.

- Vlach agrees that there are types, but he argues that the promises of the Noahic, Abrahamic, Davidic, and new covenants are not types. He also rejects what he terms typological interpretation, which he defines as interpretations that transform covenant promises into something other than what was promised.

In chapters 5-6 Vlach turns to what he describes as the hermeneutics of non-dispensationalism.

- He rejects NT priority. He defines this as the idea that the NT use of the OT involves a “radical reinterpretation” of OT prophecies (93, citing Ladd, A Theology of the New Testament, rev. ed., 373). He is right to deny that the NT “reinterprets” the OT or changes the meaning these texts originally had. But he over-reacts when he denies that that the NT teaches interpreters how to interpret the OT (see below).

- He rejects spiritualizing the promises regarding the physical creation.

- He denies that covenantal promises are types

- He denies that prophecies about events to come are types. (I would affirm this denial even while granting that these prophecies may involve people and institutions that are typological at some point in history.)

- He denies that a typical entity or institution can cancel out the fulfillment of promises regarding those entities or institutions. He helpfully quotes Craig Blaising’s opposition to when typology is “employed to contravene, suppress, or subvert the meaning of explicit covenant promise, and even more so when the NT explicitly repeats and reaffirms the same promise as declared in the covenants of the OT” (Blaising, “A Critique of Gentry and Wellum’s, Kingdom through Covenant: A Hermeneutical-Theological Response,” 117 as cited on p. 108).

- He objects to the use of the following terms to describe the NT’s interpretation of the OT: “redefine,” “reinterpret,” “transform,” “transcend,” “transpose” (114).

- Vlach is correct to say, “Matters like corporate Israel, nations, land, earthly kingdom, and physical blessings are not Jesus, but they are related to Jesus. We should understand how everything relates to Jesus without assuming all things disappear or metaphysically collapse into Him” (122).

Weaknesses

- He defines redemption and redemptive history too narrowly. Redemption encompasses the restoration of all creation and includes God’s kingdom purposes. This narrow definition of redemption is inconsistent with things Vlach says elsewhere. I think it is a place where some traditional dispensational thinking is it odds with his broader theology.

- Vlach is correct to focus on the multidimensional nature of the covenants, but in this book he only seems to speak of the Israel aspect of the covenants. If some covenant theologians err by focusing only on the salvation aspects of the covenants, dispensationalism often errs by focusing on the Israel side of things to the neglect of other aspects.

- He doesn’t always accurately represent covenant theology. For instance, presents the Covenant Theolgoy position as holding that the Moasic covennat was a restatement of the covenant of works, that the Mosaic covenant was a restatement of the covenant of grace, or that the Mosaic covenant was a restatement of both. But the Mosaic covenant as a republication of the covenant of works is controversial among covenant theologians. In addition, among most covenant theologians, the Mosaic covenant is not a restatement of the covenant of grace but is an administration of the covenant of grace.

- Sometimes Vlach’s statements about what non-dispensationalists think are too sweeping. Other times non-dispensational viewpoints are stated prejudicially; that is, they are stated in ways that I don’t think proponents of those views would hold. I should note however, that this critique can also be applied to almost every single critique of dispensationalism that I’ve read from a covenant theologian. Covenant theologians are almost always critiquing either older forms of dispensationalism or they are critquing straw men. Both sides in this debate need to do better in understanding the other side before registering their critiques.

- Vlach’s typology of the temple fails to recognize that the temple was solely and purely a symbol that would pass away. The typology of the land is different. It seems that both Vlach and the major altenatives to dispensationalism (covenant theology and progressive covenantalism) don’t recognize this difference. This causes all of these parties to err in their understading of biblical typology, though in different ways.

- Vlach over-reacts to the misuse of typology. He has some legitimate concerns. But in response, Vlach wants to limit typology to “the Mosaic Law and its elements” (108), and he wants to deny that Israel and the land are types because they are “linked with … covenants of promise.” However, David was a type of Christ even though kingship is linked to the Davidic covenant, a covenant of promise, rather than being a provision of the Mosaic Law and its elements. Thus, Vlach is drawing the definition of typology too tightly.

- This is how I woudl respond to the problem that Vlach is seeking to address:

- If someone were to say: David is a type of Christ; therefore, he will not enjoy eternal life in the new creation because Christ is the reality and the type has entirely passed away, the proper response would be to note that David was a type of Christ in his life and reign in the Old Testament. His life in the new creation is not typological.

- Likewise, Israel was a type of the church during the period of the Mosaic Covenant. Its continued existence in the new creation is not typological. The land was a type of the new creation in the period of the conquest and during Solomon’s reign, and the future fulfillment of the land promise is not typological.

- In other words, rather than denying that David or Israel or the land are types (as Vlach does), the better solution is to understand that certain types all have a time dimension to them.

- Vlach rejects that the NT should instruct us in how to interpret the OT. I understand his concern about approaches that re-interpret original OT meaning, but this is a problematic over-reaction that undercuts the sufficiency of Scripture for hermeneutics.

- Too often Vlach makes assertions rather than arguments when dealing with opposing views.

A Brief Review of the New Subscription-Based Logos Bible Software

The big news about Logos Bible Software is that it is moving to a new subscription model. I have mixed feelings about this. On the one hand, I try to avoid all subscriptions for software. On the other hand, I have an investment in Logos, and I want the company to succeed so that my investment continues to pay dividends. Here is the FAQ for the Logos subscriptions. Something that softens the change to subscription is the Legacy Fallback License. For those who have already purchased a base package, they can keep features from their subscription tier that don’t rely on the cloud or AI. The features that do require cloud and AI are specified in the FAQ. This seems to allow something akin to an occasional upgrade for those without the budget for a subscription.

Logos is touting several new features.

Synopsis Feature

The synopsis feature uses AI to summarize top search results. The summary is footnoted so that the user can jump from the summary to the resources. I like the idea. I tried several sample searches, and the results were mixed. As expected with AI-generated text, the paragraphs didn’t always cohere, were not always drawing from the sources that I would value the most, and thus did not tend to direct me to the main sources. However, by narrowing the scope of the resources being searched, I was able to generate better results.

This search on the archaeology of Jericho under the “All” tab (which searches books in my library as well as books I have not purchased) returned a critical understanding of the question.

The result was somewhat better when I limited the search to just the books I owned, but it was still drawing on sources that I would not rank highly, and it still gave a generally critical summary.

When I limited the range of the search to journals which I owned, the content was better, but the paragraph didn’t really cohere.

Perhaps this feature will continually improve as AI improves, and it would work best if run against pre-defined collections of books. But at present I probably won’t be using this feature.

Summarize Feature

An AI feature that I did find helpful was the summarize feature in the search results. Historically, the search results returned a sample of text, and by reading that sample the user decides if that resource is worth reading or not.

But by clicking on “Summarize,” an AI summary of the source is generated that provides a bigger picture summary of the source.

I found this genuinely helpful in choosing resources to pursue from search results.

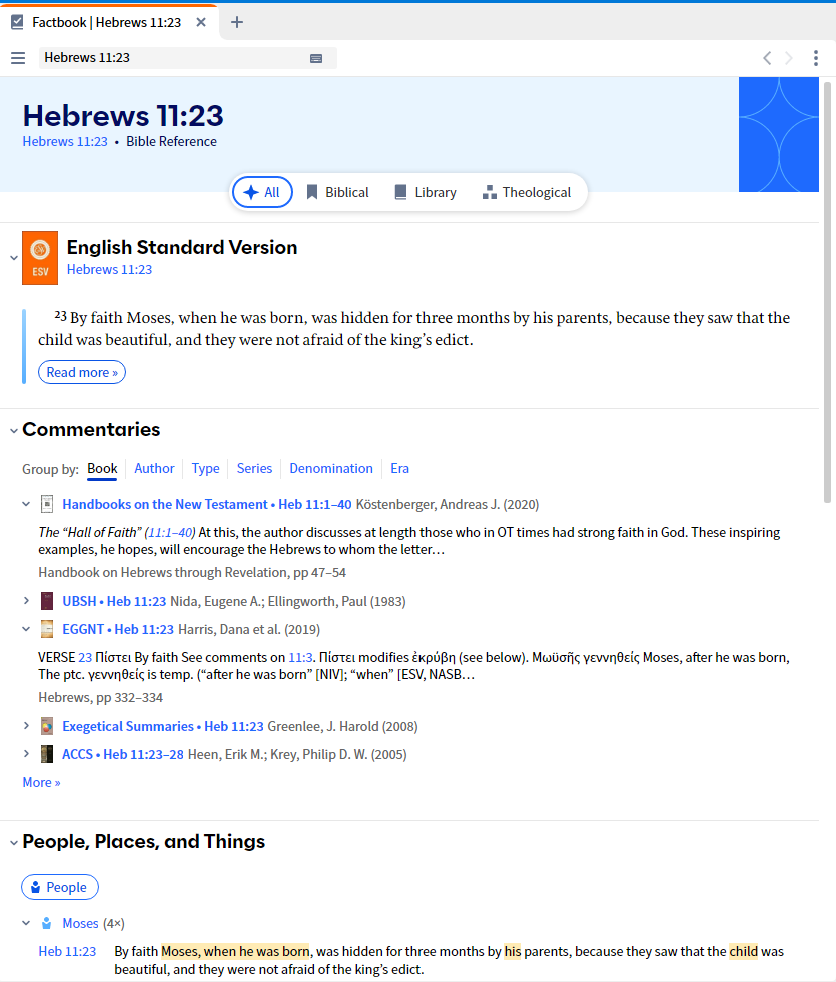

Updated Factbook

One of the challenges that comes with a large library in Logos is surfacing the right materials from the library at the right time. The Factbook helps with this.

Here are some examples of different kinds of Factbook searches:

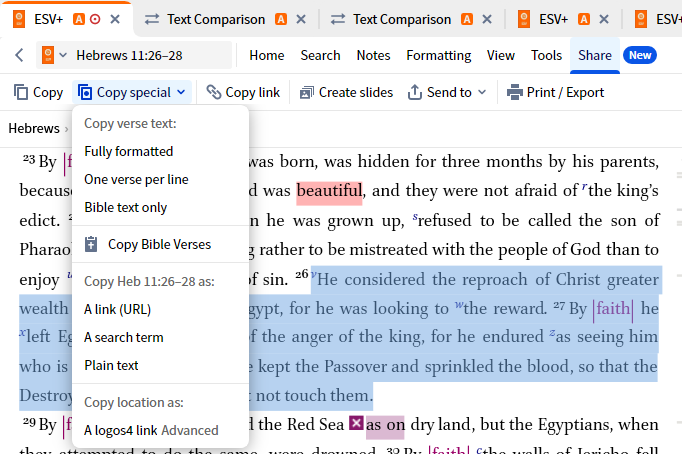

New Toolbar

The subscription version of Logos has also debuted a new toolbar. This is similar to the ribbon in Microsoft Office. Selection of different tabs reveals access to different tools. While this does mean extra clicks to access certain features, it also makes a number of features more clearly accessible. For instance, I’m glad to be able to access special copy features without having to open the copy verse pane.

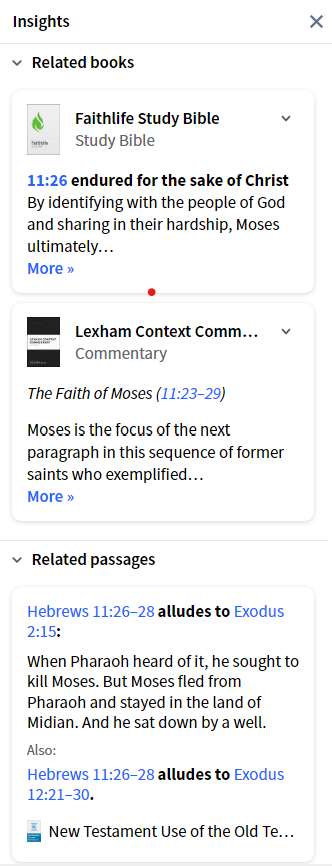

Insights

Another new feature is the Insights panel which can open on the right side of a Bible resource. It will surface a top Bible commentary, and parallel passages.

I find the Related Passages section helpful. I’d rather drop the Study Bible option. Permitting customization in which the top commentary for each book of the Bible could be selected would make this feature more useful to me.

Other Things I Liked and Areas for Improvement

The new version of Logos had a couple of other features that I liked. The program no longer needs to be restarted when changing from to or from dark mode. When text is copied from the mobile app, a citation is copied along with it. This is especially helpful because the mobile app does not consistently show page numbers.

There are a few regressions which are now areas for improvement. In Logos 10 there were several options for linking to resources. I prefer the L4 option because I can link directly to the program without internet access. In the new Logos this option does not seem to be present.

I like the bottom drawer in the mobile app and all of the functions it holds. However, when copying text, the drawer takes up too much space on the screen, and this limits how much text can be copied. It should recede entirely when text is being copied and reappear only after text has been selected. Even better, it would be good if the screen would scroll when the user selects text down to the bottom of the screen.

Pricing Info and Subscription Link

Here is the subscription pricing:

To subscribe, see here.

For more information from Logos on the subscriptions, see: https://www.logos.com/subscription-faq

The Fall 2024 Issue of the Journal of Biblical Theology and Worldview Has Been Realeased

The Fall 2024 issue of the Journal of Biblical Theology and Worldview has just been released.

I contributed three book reviews:

I would also commend Layton Talbert’s article “Adoring Shulamite as Foil to Adulterous Israel: A Canonical Theology of the Song of Songs.” This is the best article I’ve read on the Song’s theology. Talbert interacts with some of the best material I’ve read elsewhere, and he refines and extends their insights. He does this by a careful attention to details in the biblical text that require more precision in statement than is often found even in helpful articles and commentaries. This increased precision has a theological pay-off. This article deserves a wide reaidng.

A False Friend in Proverbs 18:9?

The KJV reads “He also that is slothful in his work Is brother to him that is a great waster” while the NKJV reads “He who is slothful in his work Is a brother to him who is a great destroyer,” and most modern translations are similar to the NKJV (the NRSV and CSB read “vandal” instead of “destroyer”). According to the OED, “waster” could refer to “One who lays waste, despoils or plunders; a devastator, ravager, plunderer” (s.v. waster, noun1, sense I.2.a.) or “One who lives in idleness and extravagance; one who wastefully dissipates or consumes his or her resources, an extravagant spender, a squanderer, spendthrift” (s.v. waster, noun1, sense I.1.a.). Both senses were current in the 1600s.

Interestingly, the Hebrew word being translated, מַשְׁחִית, is translated in the KJV as “destroy,” “destroyed,” “destroyer” or some variant in 10 of its 20 occurrences. Twice it is translated “destruction,” twice “corruption,” twice “spoilers” (in the sense of people spoiling the goods of an enemy), once “slay utterly,” and once “trap.” Twice the KJV translators rendered this term as “waster.” They did so in this verse and in Isaiah 54:16: “And I have created the waster to destroy.” Given then way that the KJV translators rendered this Hebrew word elsewhere, it seems likely that the sense “one who lays waste, despoils or plunders; a devastator, ravager, plunderer” is what the KJV translators intended here. However, it seems that “waster” was early misread as “an extravagant spender, a squanderer, spendthrift,” since this is the meaning ascribed to the term even in older commentators such as Matthew Henry and John Gill.

See also:

Proverbs 11:16-17 and Gender-Neutral Translations

The pattern of these two proverbs is “kind woman / cruel man // kind man / ruthless man.” By itself v. 16 could be read cynically (“A kind woman gets respect, but a cruel man gets rich” [the word “only” is not in the text]) to justify unscrupulous behavior. In conjunction with v. 17, however, the self-destructive nature of the “hard-nosed” approach to life is apparent.

Duane A. Garrett, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Songs, vol. 14, The New American Commentary (Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 1993), 126.

By translating אִישׁ in 11:17 in a gender-neutral manner—”Those who are kind” (NRSV, NIV 2011), “A merciful person” (NASB 2020), “Kind persons” (CEB)—the parallel with “A gracious woman” in 11:16 is missed. I find that too often gender-neutral translations miss how the Bible highlights men and women in its metaphors and proverbs.

Toward an Interpretation of Leviticus 18:5

וּשְׁמַרְתֶּ֤ם אֶת־חֻקֹּתַי֙ וְאֶת־מִשְׁפָּטַ֔י אֲשֶׁ֨ר יַעֲשֶׂ֥ה אֹתָ֛ם הָאָדָ֖ם וָחַ֣י בָּהֶ֑ם אֲנִ֖י יְהוָֽה׃

“So you shall keep My statutes and My judgments, which if a man does them, he shall live by them; I am Yahweh” (LSB)

Thesis: This verse promises eternal life upon obedience to the statutes and judgments of the Mosaic covenant. In fact, no one (except Christ) would ever be able to fulfill this requirement and thus no one would obtain salvation by this path.

Place of Leviticus 18 in the Structure of Leviticus

Leviticus 18 begins a major section of the book of Leviticus. Leviticus 18:5 thus stands at a strategic point in the book.

Leviticus 1-16 deals with the cultic matters that relate to entering into the tabernacle. This section climaxes with the day of atonement as recounted in chapter 16. Chapter 17 “serves as a pivot between Leviticus 1-16 and 18-26” (Averbeck, “Tabernacle,” DOTP, 820).

Jay Sklar concurs with this structure:

Like chapters 1–16; Leviticus 17 addresses issues related to the proper place of sacrifice (cf. 17:4 with 1:3; 3:2; 4:4), the proper use of blood (cf. 17:10, 12, 14 with 3:17; 7:26), the importance of addressing ritual impurity (cf. 17:15–16 with 11:24–25, 39–40; 15:31; 16:16, 19), and the application of these laws to resident aliens (cf. 17:8, 10, 13, 15 with 16:29). But like chapters 18–20; Leviticus 17 also has a prohibition against illicit cultic practices (cf. 17:7 with 18:21; 19:4; 20:2). The chapter therefore serves as a smooth transition between Leviticus 1–16 and Leviticus 18–20. [TOTC, 217]

Averbeck also notes,

On the one hand, ch. 17 looks back to chs. 1-16 in the sense that it emphasizes making offerings in the tabernacle (vv. 1-9) along with blood “atonement,” which therefore includes the prohibition against eating blood (vv. 10-16). On the other hand, the primary goal of the regulations in ch.17 is to introduce one of the major concerns of chs. 18-26: the absolute exclusivity of Yahweh worship. [NIV BTSB, 200]

Averbeck also notes that the statements, “Be holy because I, the LORD your God, am holy” and “I am the LORD (your God)” occur throughout Leviticus 18-26 but do not occur in Leviticus 17 or 27 (DOTP, 820).

Thus Leviticus 18:1-5 is the beginning section of the next major part of the book of Leviticus. Its scope, therefore, should not be reduced to the laws regarding unlawful sexual relations. Rather, these verses occur at the center of the book of Leviticus, at the center of the Pentateuch, and at the beginning of a section about holiness of life in the promised land.

It should not be surprising, therefore, that New Testament figures discerned in Leviticus 18:5 a programmatic statement regarding the Mosaic Law. Neither Jesus nor Paul was cherry-picking a random verse from the Pentateuch when he quoted Leviticus 18:5. Both recognized that Leviticus 18:5 occupies a strategic position within the structure of Leviticus and within the structure of the Pentateuch.

The Use of the OT in Leviticus 18

Nobuyoshi Kiuchi observes numerous connections between Leviticus 18 and Genesis 2-3 (ApOTC, 330-31). For instance, much of Leviticus 18 deals with forbidden sexual relations, including between men and men and between man and beast. These laws are rooted in the creation order outlined in Genesis 2:20-23. Adam’s inability to find a corresponding helper in the animal world and God’s creation of woman as the corresponding helper for man reveals the proper creation order regarding intimate relations. Leviticus 18 also refers repeatedly sexual relations in terms of uncovering nakedness. This evokes Genesis 2:25 and Genesis 3:21. Unfallen man and woman were “both naked and were not ashamed” (Gen 2:25), but after the Fall man and woman are in need of covering (Gen 3:21). Finally, just as man was sent (שׁלח) from the garden after his sin so the nations are sent out of the promised land, the analogue to Eden (Lev 18:24).

Given the extensive connections between Genesis 2-3 in this chapter, it is difficult not to read, “”So you shall keep My statutes and My judgments, which if a man does them, he shall live by them” (LSB) as an analogue to “but of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil you shall not eat, for in the day that you eat of it you shall surely die” (Gen 2:17). Since Genesis 2:17 encompassed not only physical death but also eternal death, Leviticus 18:5 may also encompass not only temporal life but also eternal life.

It is also notable that Leviticus 18:5 switches from the phrasing, “So you shall keep” to “if a man [הָאָדָ֖ם] does them. Jason DeRouchie observes, “the noun phrase ‘the man’ (הָאָדָם) in Leviticus 18:5 may be an allusion to the first man (הָאָדָם) in the garden, who himself foreshadowed Israel’s existence. God created the first man in the wilderness (Gen 2:7), moved him into paradise (2:8, 15), and gave him commands (2:16–17), the keeping of which would have resulted in his lasting life (2:17; cf. 3:24). Then, upon the man’s disobedience (3:6), God justly exiled him from paradise, resulting his ultimate death (3:23–24; cf. 3:19). This too becomes Israel’s story” (“The Use of Leviticus 18:5 in Galatians 3:12,” Them 45 [2020]: 249). DeRouchie concludes, “”The Mosaic covenant, therefore, in many ways mirrored God’s covenant with creation through Adam (Isa 24:4–6; Hos 6:7), with Yahweh’s relationship with Israel supplying a microcosmic picture of the larger relationship he has over all humanity” (“The Use of Leviticus 18:5 in Galatians 3:12,” Them 45 [2020]: 249).

Exegetical Observations on Leviticus 18:1-5

Leviticus 18:1-5 establishes that just as Adam and Eve were in a covenant relationship with Yhwh, so the people of Israel are in a covenant relationship with Israel. Twice Yhwh identifies himself with the phrase, “I am Yhwh your God” (Lev 18:2, 4). For Yhwh to be “your God” implies a covenant relationship with the people he is addressing.

John Kleinig rightly observes, “The promise of life here goes beyond mere physical survival. It has to do with the possession of God-given life in its fullness: liveliness and vitality, prosperity and blessing (Deut 30:15-20). This abundant life continues into the age to come (Jn 10:10)” (ConC, 375-76). As Kiuchi astutely observes, if eternal life is not in view, the phrase “and lives” refers to a state that “will ultimately result in death” (ApOTC, 332).

In support of the eternal life interpretation, Kiuchi observes, “In Leviticus the term ḥāyâ means to ‘live’ in the biological sense of moving freely (cf. 13:10, 14-16; 14:4-5; 16:10; Deut 8:3; Ezek. 20:11, 13, 21). However, as this life is guaranteed by the observance of these rules, and not by food, the life envisaged here must mean more than just physical life, but primarily spiritual life, a life that embraces physical life” (ApOTC, 332). Kiuchi concludes, “it is possible to read this verse as saying that by ‘and live’ the Lord intends to say that a man lives forever, on the assumption that the present life is part of eternal life (cf. Eccl. 3:11; Gen. 3:22)” (ApOTC, 332).

This interpretation is consistent with other statements in the Mosaic covenant, as Jason DeRoucie notes: “Moses frequently conditions life and blessing/good (Lev 26:3–13; Deut 28:1–14), death and curse/evil (Lev 26:14–39; Deut 27:11–26; 28:15–68), on a perfect keeping of all the law (Deut 11:26–28; 30:15–19; cf. e.g., 5:29; 6:25; 8:1; 11:32; 26:18) with all one’s heart and soul (4:29; 6:5; 10:12; 11:13; 13:3; 26:16; cf. 30:2, 6, 10). By their pursuing God’s standard of ‘righteousness’ (צֶ֫דֶק, 16:20) and by their keeping his whole commandment manifest in the various statutes and rules, the Lord would preserve their lives (6:24), they would enjoy the status of ‘righteousness’ (צְדָקָה, 6:25; cf. Ps 106:30–31), and they would secure lasting ‘life’ (Deut 8:1; 16:20; 30:16)” (“The Use of Leviticus 18:5 in Galatians 3:12,” Them 45 [2020]: 247). Though many of these statements emphasize the temporal blessings that Israel would receive, those blessings were to anticipate the blessings of eternal life. Thus DeRouchie notes, “”The community needed God to preserve their present lives (cf. Deut 4:4; 5:3; 6:24), and the blessings they sought included temporal provision and protection (see esp. Lev 26:3–13; Deut 28:1–14). Nevertheless, in a very real sense the “life” Moses was promising also included a soteriological and eschatological escalation beyond their present state—one that he could contrast with being “cut off from among their people” (Lev 18:29)” (“The Use of Leviticus 18:5 in Galatians 3:12,” Them 45 [2020]: 247).

DeReouchie goes on to observe, “In light of the above, the prepositional phrase in the clause “they shall live by them” in Leviticus 18:5 most likely includes a sense of instrumentality (i.e., “by means of the statutes”) and not just locality (i.e., “in the sphere of the statutes”)” (“The Use of Leviticus 18:5 in Galatians 3:12,” Them 45 [2020]: 247).

Many interpreters (Gathercole, Moo, and others) hold that Leviticus 18:5 was speaking typologically about life in the land but that later OT passages, NT texts, and rabbinic writings interpret the typological in light of what it typified (that is, eternal life) or that they expanded the scope. It would be better, however, to understand Ezekiel, Jesus, and Paul as correctly interpreting Leviticus 18:5.

Reception History

Tg. Ps.-J. and Tg. Onq. identify the life in this verse as “eternal life” (Hartley, WBC, 282). Likewise, Damascus Document and Psalms of Solomon understand life in this passage to be eternal life (Rosner, Paul and the Law, NSBT, 63). Jewish intertestamental and rabbinic literature is not always correct in their interpretations, but these sources do provide early evidence for the plausibility of the eternal life reading

That this covenant promised eternal life on the condition of perfect obedience is a strand that runs through the Protestant interpretive tradition. As John Calvin observed, “If someone expresses the Law of God in his life, he will lack nothing of the perfection required before the Lord. In order to certify that, God promises to those who shall have fulfilled the Law not only the grand blessings of the present life, which are recited in Lev. 26:3–13 and in Deut. 27:1–14, but also the recompense of eternal life (Lev. 18:5)” (“Calvin’s Catechism (1537),” in Reformed Confession, 1:364). Calvin reiterates this understanding in the Institutes: “We cannot gainsay that the reward of eternal salvation awaits complete obedience to the law, as the Lord has promised”—while also observing, “Because observance of the law is found in none of us, we are excluded from the promises of life, and fall back into the mere curse” (Battles translation, 1:351, 352; 2.7.3).

Andrew Bonar understands the life in this verse to be eternal life, and he concludes: “so excellent are God’s laws, and every special, minute detail of these laws, that if a man were to keep these always and perfectly, this keeping would be eternal life to him.” Noting the quotation of this verse in Romans 10:5 and Galatians 3:12, Bonar finds this interpretation “to be the true and only sense here” (Leviticus, 329-30).

Similarly, Geerhardus Vos quotes this verse in support of the claim that “even after the covenant of works is broken, perfect keeping of the law is presented as a hypothetical means for obtaining life, a means that must work infallibly” (Reformed Dogmatics, 41:1).

Old Testament Use of Leviticus 18:5

Simon Gathercole identifies Ezekiel 20 as the “first commentary on Leviticus 18:5 (“Torah, Life and Salvation,” in From Prophecy to Testament, 127; cf. Kleinig, ConC, 375; Moo, BECNT, 221). In Ezekiel 20:11, 13, 21 Yhwh refers to the laws of the Mosaic covenant as those “by which, if a man does them, he will live by them” (LSB). Disobedient Israel is then given over to “statutes that were not good and rules by which they could not have life,” which is probably a reference to giving them over to idolatrous ways (Calvin, Commentary, 2:315; Poole, Annotations, 2:721; Owen, Works, 22:465-66; KD 9:157; Fairbairn, Ezekiel, 220-22; Vos, Biblical Theology, 144; Feinberg, Ezekiel, 112; Cooper, NAC, 205; Alexander, REBC, 749). To say that idolatrous ways were those “by which they could not have life” is an understatement as idolatry brings eternal death. Also, the contrast between eternal death and life indicates that the life in view is eternal life. Finally, this passage foretells a restoration of Israel in the new creation. Ezekiel 20 seems, therefore, to interpret life in Leviticus 18:5 as eternal life.

Nehemiah 9:29 also alludes to Leviticus 18:5 (Kleinig, ConC, 375; Moo, BECNT, 221). Once again, the laws of the Mosaic covenant are referred to as that “by which if a man does them, he shall live” (LSB). What follows are temporal punishments. This does not invalidate the thesis, for as Kiuchi above noted the eternal life in view would include this present life also.

New Testament Use of Leviticus 18:5

Matthew 19:17

When the rich young man asked Jesus, “Teacher what good deed must I do to have eternal life?” (Mt 19:16) Jesus responded in a twofold manner. First, he established that only God is good (Mt 19:17). Second, he said, “If you would enter life, keep the commandments.” (Mt 19:17). The commandments that are then detailed are the from the Decalogue to which is added the second great commandment (from Lev 19:18).

Calvin understands Jesus to teach “that the Law teaches how men may obtain righteousness by works, and yet that no man is justified by works, because the fault lies not in the doctrine of the Law, but in men” (Harmony of the Evangelists, 3:60). It will not do to say that Jesus simply answers the rich young man according to his own viewpoint. Though the young man’s viewpoint provides the framework for Christ’s answer, Jesus was not simply accomodating himself to this young man. Christ both teaches that eternal life can in theory be obtained by obedience to the law and that in fact it cannot be so obtained since no one is good but God alone.

Luke 10:28

Just preceding the Parable of the Good Samaritan, a lawyer asked Jesus, “Teacher, what shall I do to inherit eternal life?” (Lk 10:25). When Jesus asked the man what the Law of Moses said, he responded by citing the two great commandments. To which Jesus, responded, “You have answered correctly; do this, and you will live” (Lk 10:28). The two great commandments summarize the Mosaic Law, and Jesus echoed Leviticus 18:5 in affirming this to be the right answer (Crowe, Perfect Life, 81). In context, this is eternal life that Jesus is speaking of. However, the way Jesus phrased this affirmation implied that the lawyer was not yet fulfilling the law and thus still lacked eternal life (Garland, 438-39). The lawyer, for his part, recognizes that he cannot keep the Mosaic Law without narrowing its requirements. Thus obedience to the Mosaic covenant is seen as a potential path to eternal life, but not one that any sinner will achieve. As Calvin says, “for the reason why God justifies us freely is, not that the Law does not point out perfect righteousness, but because we fail in keeping it, and the reason why it is declared to be impossible for us to obtain life by it is, that it is weak through our flesh, (Rom. 8:3.) So then these two statements are perfectly consistent with each other, that the Law teaches how men may obtain righteousness by works, and yet that no man is justified by works, because the fault lies not in the doctrine of the Law, but in men” (Commentary on a Harmony of the Evangelists, 60).

Galatians 3:12

In this context Paul establishes first that those who do not keep all of the Mosaic Law fall under its curse (Gal 3:10 citing Dt 27:26). To this he opposes Habakkuk 2:4, “The righteous shall live by faith” (Gal 3:11). This observation is in service of the argument that “no one is justified before God by the law” (3:11) since “The law is not of faith” (3:12). To establish the provided alternative (and impossible, cf. 3:10) path to eternal life, Paul quotes Leviticus 18:5, “The one who does them shall live by them.”

Bryan Estelle observes, “When we come to Paul’s use of these terms and explore the context in which he understood the promise of life conditioned upon obedience, he clearly parsed that ‘life’ as ‘the life of eternity’ or ‘the world to come'” (“Leviticus 18:5 and Deuteronomy 30:1-14 in Biblical Theological Development,” in The Law Is Not of Faith, 110).

Some claim that when Paul cites Leviticus 18:5 he is doing to so to critique a misinterpretation of the verse (Sklar, TOTC, 229). However, Paul was not citing a misinterpretation of Leviticus 18:5 but was citing the verse itself. In context, Paul was contrasting the Mosaic and new covenants. He could do this by quoting verses from the Pentateuch because the Mosaic writings contain not only the provisions of the Mosaic covenant but statements of its inadequacy (due to human sinfulness) and predictions of the coming new covenant and its provisions. In addition, what Sklar identified as a misinterpretation seems to be the interpretation Jesus gave to the verse in Luke 10:28.

Romans 10:5

In context Paul is discussing two ways of pursing righteousness. The Gentiles pursued righteousness by faith and attained it, but the Jews pursued righteousness by works and stumbled over the stumbling stone, that is Christ. By seeking to establish their own righteousness, they did not receive Christ’s righteousness. They failed to see that Christ was the end (the fulfillment, terminus, and completer) of the law for the purpose of bringing righteousness to everyone who believes. In other words, justification through faith in Christ is what the Mosaic Law was always pointing to and the coming of Christ brought the Mosaic law to a point of completion.

In Romans 10:5-9 Paul establishes his argument with Scripture. He quotes Leviticus 18:5 to establish that the Mosaic covenant promised righteousness and eternal life based on doing the commandments. To this he opposes Deuteronomy 30, in which the people are told that the word of faith can bring them salvation. Paul is not pitting Moses against himself here. In context Deuteronomy 30 establishes that the Mosaic covenant would not save the Israelites; it predicted they would come under its covenant curses. Therefore, Deuteronomy 30 points the people forward to a coming new covenant, the benefits of which could be obtained by faith by anyone in any era who called on the Lord by faith.

Romans 7:10

Though Paul does not quote Leviticus 18:5 in Romans 7:10, the statement “the very commandment that promised life proved to be death to me” seems to allude to it (Rosner, Paul and the Law, NSBT, 66). Leviticus 18:5 was a promise of (eternal) life on the basis of obedience. However, as Paul makes clear in Romans 7, no one (other than Christ) is able to keep the Law and obtain life by that promise.

Proposed Interpretation of Leviticus 18:5

This verse promises eternal life upon obedience to the statutes and judgments of the Mosaic covenant. In fact, no one (except Christ) would ever be able to fulfill this requirement and thus no one would obtain salvation by this path. Something the Mosaic Law itself made clear. However, the “except Christ” is a very important exception. Christ was born under this Law, and he fulfilled it in our place.

Objections to the Proposed Interpretation of Leviticus 18:5

Obj. 1: The claim that eternal life is promised upon obedience to the Law is contrary to the doctrine of justification by faith alone

Mark Rooker observes that verse 5 ” has been interpreted as rewarding salvation to those who keep the commandments,” but he rejects this interpretation on the grounds that it is “in conflict with the doctrine of justification by faith” (NAC, 240).

Ans. Galatians 3:12 and Romans 10:5 cite this verse as pointing to a way of justification by the works of the law. These passages are clear that no one will actually be justified in this way. But it is nonetheless presented as a hypothetical way of obtaining righteousness.

Obj. 2: Israel had already been graciously redeemed by Yhwh

This is how Jay Sklar argues: “It is crucial to understand that this verse does not mean the Israelites were to earn relationship with the Lord through their obedience. The larger context makes clear that the Lord gives the Israelites the law after he redeemed them (cf. Exod. 1–19 with Exod. 20–23). The law regulates this relationship; it does not create it. As in the New Testament, relationship with the Lord is always grounded in his gracious redemption (cf. Rom. 5:8)” (Sklar, TOTC, 229).

Ans. This is to confuse the type and the reality. Physically and typologically Israel had been redeemed from slavery in Egypt. The very structure of the exodus account reveals that the physically and typologically redeemed Israelites still stand in need of redemption.

Exodus 15:1-21 marks the end of Israel’s redemption from Egypt. These verses mark the beginning of a transitional section between that redemption and the giving of the Mosaic covenant (ch 19ff.). This transitional section begins with three pericopes in which the people are grumbling against Yhwh and against Moses regarding food and water. These three pericopes reveal that even though Israel was physically redeemed from Egypt, the Israelites were still in need of new hearts. They still needed redemption from sin.

At the end of the first of these grumbling pericopes, the text provides a brief preview of the Mosaic covenant: “There Yhwh made for them a statute and a rule, and there he tested them, saying, ‘If you will diligently listen to the voice of Yhwh your God, and do that which is right in his eyes, and give ear to his commandments and keep all his statutes, I will put none of the diseases on you that I put on the Egyptians, for I am Yhwh, your healer'” (ESV, adj.).

Note the conditional nature of the statement: If Israel keeps Yhwh’s law, then God will keep the judgments of Egypt from Israel. The implication is that if Israel does not keep Yhwh’s law they will receive the judgments of Egypt themselves. A case and point would be the locust plague Israel experienced as recorded in Joel 1.

Note also Yhwh’s identification of himself at the end of this statement, “for I am Yhwh, your healer.” This is given as a reason for why Yhwh will not bring the diseases of Egypt upon Israel. It is not a statement that Yhwh will heal Israel from these diseases.

The fact that this pericope is followed by two more in which Israel grumbles at Yhwh demonstrates that the nation did not come to Yhwh for healing. Israel’s rebellion at the golden calf incident and in Numbers shows that Israel still remained in need of healing.

Jason DeRouchie observes, “By Leviticus 18, the narrator has highlighted how the people have tested God seven times since leaving Egypt, and by the time the ten spies fail to believe the Lord, the total testings would be ten (Num 14:21–23).24 Thus, Moses rightly labels them “stubborn” (Exod 32:9; 33:3, 5; 34:9; Deut 9:6, 13; 10:16; 31:27), “unbelieving” (Num 14:11; Deut 1:32; 9:23; cf. 28:66), and “rebellious” (Num 20:10, 24; 27:14; Deut 9:7, 24; 31:27; cf. 1:26, 43; 9:23). … The cry, “Do this law so that you may live!” came to a primarily unregenerated community” (“The Use of Leviticus 18:5 in Galatians 3:!2,” Them 45 [2020]: 248).

Thus, the Israelites whom Moses addressed in Leviticus 18:5 were still in need of eternal life.

Obj. 3: The sacrificial system would have dealt with the problem of imperfect obedience, thus enabling the Israelites to keep Leviticus 18:5

Jason DeRouchie responds to this claim by observing, “If, as I have argued, most original recipients of Moses’s words were unregenerate, a call to “do in order to live” would have resulted in nothing less than a type of legalism for the majority, as the ‘gracious character of the Levitical system’ would be inoperative without the feeling of guilt, confession, and trust (Lev 5:5–6; Num 5:6–7)” (“The Use of Leviticus 18:5 in Galatians 3:!2,” Them 45 [2020]: 251, quoting Jim Hamilton to critique his view).

The regenerate in Israel were to continue to practice the sacrifical system, but they should have realized that repeated animal sacrifices could not ultimately atone for their sin. They should have been looking forward to the new covenant sacrifice of the promised Seed.

Obj. 4: An offer of eternal life based on obedience to the law cannot be made because the Israelites (and all mankind) are already born sinners as a result of Adam’s sin

Ans. 1: In actual fact no sinner would be saved by their personal obedience to the Mosaic law because no sinner could meet the requirement of this covenant. However, this very fact reinforces the inability of sinners to be saved by the works of the Law.

Ans. 2: The New Testament does not present Christ as being born under the Adamic covenant and keeping the requirements of the Adamic covenant in our place for salvation. That covenant was already broken by Adam. The New Testament presents Christ as being born under the Mosaic Law and keeping the requirements of the Mosaic Law for our salvation (Gal 4:4). if obedience to the Mosaic Law could not bring salvation, how could Christ’s obedience to that Law bring us salvation?

Obj 5: The Mosaic Covenant is an administration of the covenant of grace and thus cannot be a works covenant

Ans. 1: This presumes that there is a single overarching covenant of grace of which all the biblical covenants (save the Adamic covenant) are administrations. However, there are several factors opposed to this presumption. (1) It is difficult to establish the single, overarching covenant of grace position exegetically. (2) There is significant exegetical evidence for the Mosaic covenant as being in some way a works covenant, and while there are various ways to integrate this evidence into an overarching covenant of grace view, the exegetical data and theological construction do stand in some tension with each other. (3) There are better models which better account for the data.

Ans. 2: There are ways for those who hold to a unitary covenant of grace to hold that the Mosaic Covenant is in some sense a covenant of works. These approaches have their own complications, but it allows certain covenant theologians to handle the exegetical data of Leviticus 18:5 and its co-texts well without abandoning their system of covenant theology.

Unless otherwise noted, Scripture quotations are from the ESV.

The quotation of a source above does not mean that source is complete agreement with the arguement I am making. For instance, Calvin’s views of law and covenant have some complexity to them. Likewise, Estelle’s view is complicated; he holds that the “temporal life promised in the Mosaic covenant portended and typified the greater ‘eternal life'” but that this is not “merely and exclusively a typological arrangement.” (“Leviticus 18:5 and Deuteronomy 30:1-14 in Biblical Theological Development,” in The Law Is Not of Faith, 118).

- « Previous Page

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- …

- 43

- Next Page »