First, we must understand that as long as Christ remains outside of us, and we are separated from him, all that he has suffered and done for the salvation of the human race remains useless and of no value for us. Therefore, to share with us what he had received from the Father, he had to become ours and to dwell within us. For this reason, he is called ‘our Head’ [Eph. 4:15], and ‘the first-born among many brethren’ [Rom. 8:29]. We also, in turn, after said to be ‘engrafted into him’ [Rom 11:17], and to ‘put on Christ’ [Gal. 3:27]; for, as I have said, all that he possess is nothing to us until we grow into one body with him.

Calvin, Institutes, 3.1.1.

McGraw, Ryan, trans. “Johannes Wollebius’s Paecognita of Christian Theology from

McGraw, Ryan, trans. “Johannes Wollebius’s Paecognita of Christian Theology from  The thesis of Burer and Wallace in their NTS article is that one should take “

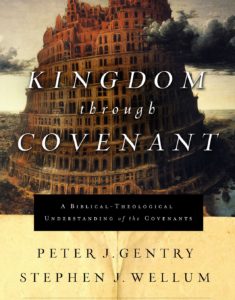

The thesis of Burer and Wallace in their NTS article is that one should take “ In this volume Wellum and Gentry embark on the ambitious project of laying out a third way between covenant theology and dispensationalism. They label their position New Covenant Theology or Progressive Covenantalism (others who hold a similar position are Tom Wells, Fred Zaspel, John Reisinger, Thomas Schreiner, and Jason Meyer). [Update 4/21/16: The authors wish to distinguish PC from NCT. The two share some similarities, but they do not wish them to be equated. Since Schreiner and Meyer both contribute to the new book on

In this volume Wellum and Gentry embark on the ambitious project of laying out a third way between covenant theology and dispensationalism. They label their position New Covenant Theology or Progressive Covenantalism (others who hold a similar position are Tom Wells, Fred Zaspel, John Reisinger, Thomas Schreiner, and Jason Meyer). [Update 4/21/16: The authors wish to distinguish PC from NCT. The two share some similarities, but they do not wish them to be equated. Since Schreiner and Meyer both contribute to the new book on  One question I face in class as a church historian is, ‘If doctrine develops, does this mean that what unites us to Christ changes over time too?’ This is an excellent question and, indeed, a rather obvious one when one is investigating the history of doctrine. Two things need to be borne in mind here.

One question I face in class as a church historian is, ‘If doctrine develops, does this mean that what unites us to Christ changes over time too?’ This is an excellent question and, indeed, a rather obvious one when one is investigating the history of doctrine. Two things need to be borne in mind here.