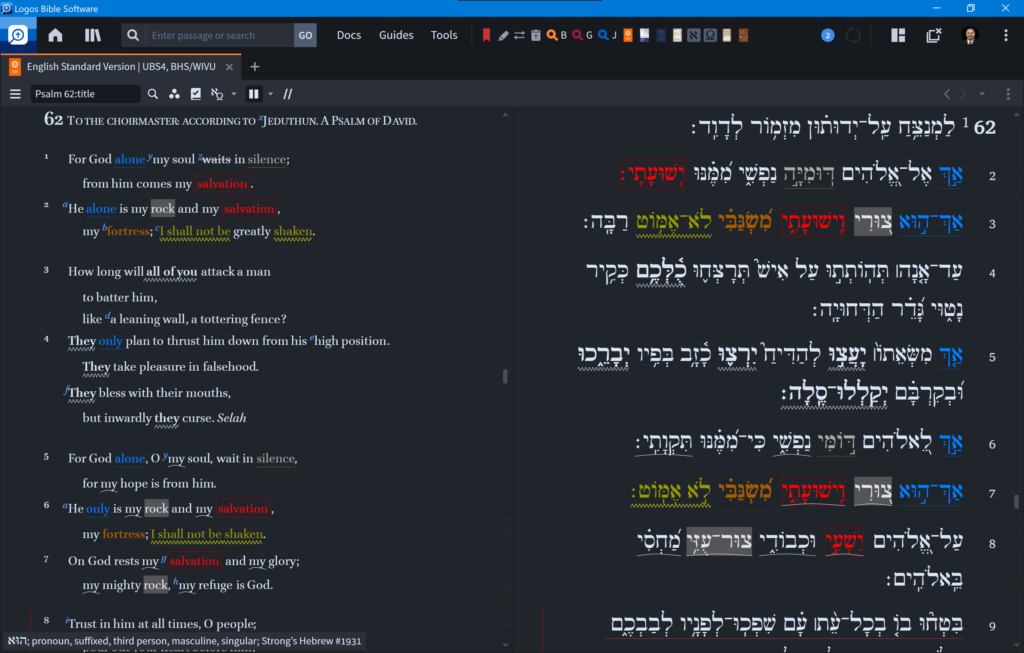

The blessings of Israel listed in Romans 9:4-5 connect with the great failure of Israel recorded in 9:30-10:4. The Israelites are blessed because of their descent from the patriarchs. But the great climatic blessing is that the Messiah, who is “God over all,” descended from the Israelites in his humanity.

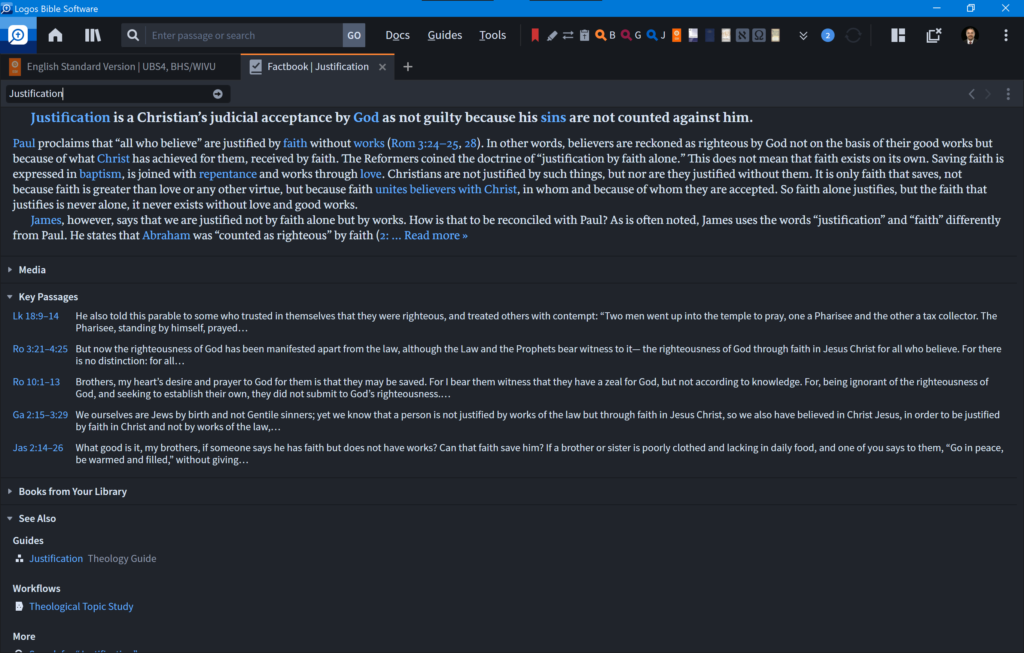

This climatic blessing encompasses all the previous blessings. Jesus is the fulfillment of the covenants, of the giving of the law, of the worship, and of the promises. “Christ is the end of the law for righteousness to everyone who believes” (Rom. 10:4). He is also the true Son of God and the radiance of the glory of God who dwelt in their midst.

But instead of recognizing Jesus as the greatest of their blessings, Israel stumbled over him “as a stumbling stone and a rock of offense” (Rom. 9:32-33). Why? Because the blessing of the covenants, the law, and the worship “they did not pursue … by faith” but by works (Rom. 9:32).