Waddington, Jeffrey C. “Which Comes First, The Intellect or the Will? Alvin Plantinga and Jonathan Edwards on a Perennial Question,” The Confessional Presbyterian 11 (2015): 121-28, 252-53.

Alvin Plantinga, in Warranted Christian Belief, proposes a concurrentist model of the relation between the intellect and the will while identifying the position of Jonathan Edwards as intellectualist, or giving priority to the intellect. Waddington argues that Edwards’s position was closer to Plantinga’s than Plantinga realized.

In the course of the article Waddington helpfully classifies various positions on the relation of the intellect and will. The first noted is “absolute intellectualism,” a position associated with Thomas Aquinas. On this view “the will is considered blind, and is seen as a slave of sorts to the intellect.” A second position is “functional intellectualism.” In this view the intellect is primary because it presents the will with the “object to which it is either attracted or repulsed.” But ontologically the will and intellect are equals. Waddington notes this view is akin to the Trinity in which each of the persons are ontologically equal while a functional order among the members exists. A key difference between these two positions is that the sin has only affected the intellect in the first, since the will is a slave to the intellect. But on the second view, both intellect and will are affected by sin and in need of regeneration. A third position is “scholastic voluntarism.” On this view the will takes such priority that it is “self-determining.” A fourth position is “Augustinian voluntarism.” In this view, the will is the orientation of the person toward or away from God. This orientation his primacy over the intellect. Finally, there is the concurrentist position is which there is no primacy of intellect or will over the other.

Though Plantinga identified Edwards as an intellectualist, Edwards scholars such as Norman Fiering and Allen Guelzo have identified Edwards as an Augustinian voluntarist. Waddington notes that this is a valid option, and the view that he had held. However, he now recognizes the legitimacy of functional intellectualism to describe Edwards. Both categories seem to fit elements of Edwards work. In the end, however, Waddington now thinks that Edwards fits best into the concurrentist position

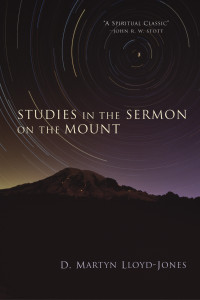

Here once more we are reminded that our Lord’s method must ever be the pattern and example for all preaching. That is not true preaching which fails to apply its message and its truth; nor true exposition of the Bible that is simply content to open up a passage and then stop. The truth has to be taken into the life, and it has to be lived. Exhortation and application are essential parts of preaching. We see our Lord doing that very thing here. The remainder of the seventh chapter is nothing but a great and grand application of the message of the Sermon on the Mount to the people who first heard it, and to all of us at all times who claim to be Christian.

Here once more we are reminded that our Lord’s method must ever be the pattern and example for all preaching. That is not true preaching which fails to apply its message and its truth; nor true exposition of the Bible that is simply content to open up a passage and then stop. The truth has to be taken into the life, and it has to be lived. Exhortation and application are essential parts of preaching. We see our Lord doing that very thing here. The remainder of the seventh chapter is nothing but a great and grand application of the message of the Sermon on the Mount to the people who first heard it, and to all of us at all times who claim to be Christian.