The argument that God’s integrity is at stake if the land promise made is not fulfilled for the nation of Israel fails to resonate with Progressive Covenantalists because of their view of the covenants.

Wellum writes, “There is a sense in which we agree with Michael Horton that Israel forfeited the promise of the land because of her disobedience, hence the reason for the exile.” However, in another sense Jesus as the “greater than Israel” will bring about the land promise (in the new creation) (Kingdom through Covenant, 706).

This view is explained by the Progressive Covenantalist position that the biblical covenants are neither conditional nor unconditional but are in some sense both (Ibid., 120-21; 285-86, 609-10, 634, 705). Wellum notes, “Viewing the biblical covenants as either unconditional or conditional is not quite right.” There are both conditional and unconditional elements in all of the covenants resulting in “a deliberate tension within the covenants.” One the one hand, the covenants reveal God and his promises. “On the other hand, all the biblical covenants also demand an obedient partner” (Ibid., 609-10).

Thus:

In this sense there is a conditional or bilateral element to the covenants. This is certainly evident with Adam as he is given commands and responsibilities to fulfill, with the expectation that he will do so perfectly. . . . Furthermore, in the Noahic covenant, obedience is also demanded, which is true of Abraham, the nation of Israel, David and his sons, and in the greatest way imaginable in the coming of the Son, who obeys perfectly and completely. . . . Yet as the biblical covenants progress through redemptive-history, this tension grows, since it becomes evident that it is only the Lord himself who remains the faithful covenant partner. [Ibid., 610.]

Likewise, Ardel Caneday claims that the division of covenants into the categories of “unconditional” and “conditional” is “too stark and simplistic” (“Covenantal Life with God from Eden to Holy City,” in Progressive Covenantalism, 101).

He elaborates:

If we use unconditional, should it not refer to God’s establishment of all his covenants with humans? Was not God’s choosing of Abraham and of Isaac not Ishmael, and of Jacob not Esau, unconditional (cf. Rom 9:6-24)? As for conditional, the term refers to the covenantal stipulations placed upon humans with whom God enters covenant, and which do not jeopardize fulfillment of any of God’s covenants. God obligates humans to obey what he stipulates in his covenants, and all whom he desires to enable do obey. [Ibid., 102]

This is, to use Caneday’s words, “too stark and simplistic.” The best of those who recognize the existence of both unconditional and conditional covenants are more nuanced about precisely what these labels do and do not refer to.

For instance, Jonathan Lunde maintains the distinction between “the ‘royal grant’ or ‘unconditional’ covenant” and “a ‘conditional’ or ‘bilateral’ covenant.” But Lunde does not dispute Caneday’s point that the choosing of the covenant partner is unconditional: “[T]he covenants are always grounded and established in the context of God’s prior grace toward the people entering the covenant, even in the case of the conditional variety” (Following Jesus, the Servant King, 40).

Nor does Lunde dispute that all covenants have “covenant stipulations”: “That is not to say that there are no demands placed on people in a grant covenant. Such are always present” (Ibid., 39).

The terms conditional and unconditional relate not to the selection of the covenant partner or to the presence of stipulations, as Caneday argued. Rather, conditional and unconditional identify whether the fulfillment of the covenant depends upon the promises of God alone or upon the obedience to the covenant stipulations. The Noahic covenant is a case in point. While acknowledging the existence and importance of covenantal stipulations in the Noahic covenant, Lunde maintians that “its benefits are unconditional, grounded solely in God’s commitment to provide them” (92). If the benefits were conditional upon the obedience of the covenant partner, then we would continually be in danger of another worldwide flood.

This is part of a series of posts on Progressive Covenantalism and the land theme in Scripture:

Progressive Covenantalism and the Land: Making Land Relevant (Part 1)

Progressive Covenantalism and the Land: Progressive Covenantalism’s View (Part 2)

The Theological Importance of the Physical World

Eden, the New Jerusalem, Temples, and Land

Rest, Land, and the New Creation

Distinguishing the Kingdom Jesus Announced and the Sovereign Reign of God over All

Land, the Kingdom of God, and the Davidic Covenant

Progressive Covenantalism, Typology, and the Land Promise

Was the Promised Land a Type of the New Creation?

How Do OT Promises and Typology Relate to Each Other?

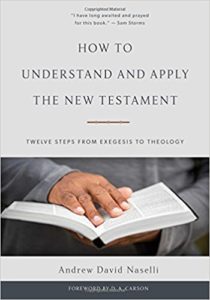

Andy Naselli has just had published a book on interpreting the New Testament:

Andy Naselli has just had published a book on interpreting the New Testament: